Italy’s population is shrinking dramatically. What are the consequences of depopulation? Is it an opportunity for foreigners to live in Italy?

Depopulation of villages

I went to a village in the northern Apennines for ten days to get a taste of what it is like in a shrinking village. My conclusion is that with the disappearance of human habitation in rural areas, the risk is that Italy will lose its age-old identity.

You perhaps can provide the solution. Read more about living in the country side and in a house for 1 euro.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Rural depopulation

Cerignale (pronunciation: cheh-reen-ah-leh) is one of the many municipalities in Italy that is chronically shrinking. They are known as depopulating villages, an European phenomenon. In municipalities with fewer inhabitants each year, stores close and eventually schools, which in turn leads to even more residents quitting. Depopulation occurs mainly in rural areas.

Depopulation has taken the greatest forms in southern Europe. In Italy, some 5000 villages (out of a total of about 8000 municipalities) know the problem of chronic depopulation.

The reason behing depopulation is that the importance of agriculture has declined, and above all that the population is falling dramatically. This, in turn, is due to an aging population. The high death rate is accompanied by a very low birth rate, a disastrous combination. In the process, there is relatively little immigration.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Also read: Houses in Italy for 1 euro: what is it and where can I buy them?

The fact that residents are leaving the Italian countryside, hills and mountains is a phenomenon that has been going on for at least 40 years, but we are now close to the denouement.

After the stores, the school, the pharmacist, the church follows and will close her doors. Gradually the church processions will come to an end as also the house blessings. The heart of the village will slowly stop beating. No communal dinners will held in the central square. The solidarity will dissolve. It will also be over and done with traditional occupations. And who will preserve local agricultural products and ‘typical’ dishes?

I stayed in Cerignale for ten days in 2021. In the village (even though Cerignale is officially a municipality) I occupied a restored stone house, directly behind the only village store. I also made a short video report of it, that you can view here (and don’t mind the subtitles):

Castelli surname

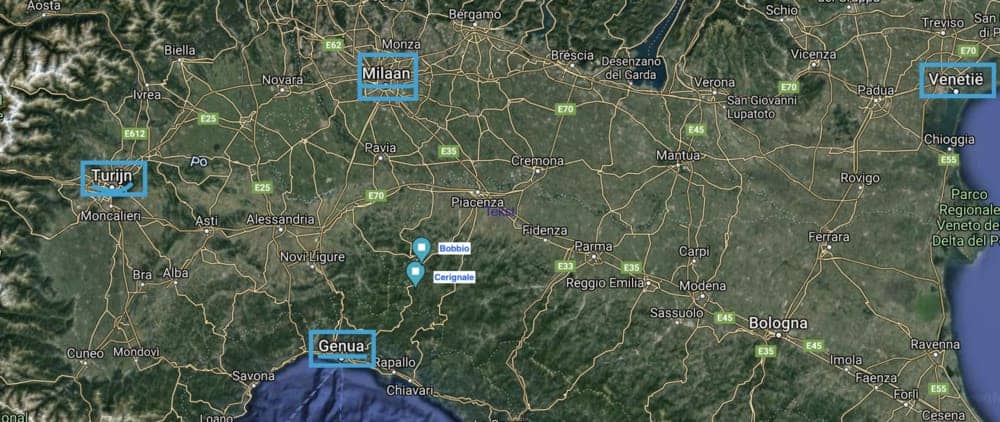

Cerignale is located at an altitude of 750 meters in a wooded area and in the basin of the Trebbia River. The municipality (including twelve hamlets) has an area of 31 square kilometers. Genoa (70 km) is an hour’s drive away as is Bobbio (23 km) -since in October 2020 a bridge over the Trebbia collapsed. To get to the main (winding two-lane) road between Genoa and Bobbio, you have to spend ten minutes on a tricky mountain road.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Massimo Castelli is the part time mayor of Cerignale. He was also born here. That also proves his surname. It is typical for this part of the Emilia-Romagna region. Castelli shares the name with 36 percent of his fellow villagers (data from the Italian Office of Statistics).

“The yearly Madonna celebration is a good indicator. This year a Mass was celebrated in the morning and a Rosary prayer in the afternoon. When I was young, the feast lasted two to three days,” says the 59-year-old mayor. “We did have a procession and I can remember that when the head of the procession had arrived at the church, we were still in the village at the back of the procession, hundreds of meters away.”

One hundred years ago, Cerignale was home to 1,200 people. But a couple of waves of immigration, first to America, later to the industrial centers of northern Italy, literally decimated the population.

Where the elementary school once was, the municipality is now located. In addition to Massimo Castelli, a full-time administrative worker, a part-time bookkeeper (two mornings), a technical man (two mornings) and a handyman work out there. The building also houses the post office, which is staffed three mornings a week.

There is one store, run by Bruna Nobile. You get bread, toilet paper and the coffee comes from a coffee cup machine. A hotel-restaurant is run by 91-year-old Teresa Castelli. The village is doomed to disappear, or at best to live on as a vacation village in the summer. The soul is disappearing.

“Depopulation leads to the loss of culture and identity, the shared history of a country,” Castelli says. In a few generations, two thousand years are jettisoned. “Traditions and customs are lost, but also crafts, food products and the way they are prepared. Local specializations are in danger of disappearing.”

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Natural disasters

The landscape as we know it is also disappearing. “The famous hills of Tuscany with vines, olive trees in line, cypresses and pine trees exist only because of man’s intervention on nature. If you don’t do anything about it, you stop farming, the landscape will soon become wild. This is also a danger. It leads to natural disasters, because, among other things, the water system and the forest are no longer properly maintained.

The territory is a given, but the population is dynamic,” Castelli says. “We can turn the tide if there are targeted policies, including European ones.” He thinks of start-up subsidies and other (financial) incentives to attract people. After all, rural areas also have a lot to offer, such as space, nature and healthy air.

A key priority of the European Union is the green economy to ensure that our continent is carbon-free within 30 years. According to Castelli, Brussels does not sufficiently integrate saving the rural area into its ‘green’ plans. “Cerignale is autonomous in terms of energy,” the mayor explains. “We have in the municipality two small hydroelectric plants, where we give the excess energy to the grid. Thus, 35,000 euros flow annually into the municipal coffers.” Where the land is hilly, it can become autonomous in this way. This will help to meet the climate targets sooner.

During the corona crisis, the value of suburban living suddenly became apparent. But that did not tangibly lead to permanent repopulation. “All the media wrote as if there was a rush to the countryside, but those few people who stayed after the summer left immediately when the first snow came down,” says Stefania Malaspina.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Ultra broadband

There are also drawbacks to living in the country. Communication is difficult: both the roads and the Internet are a bane. For internet, residents must rely on a satellite connection. As long as internet remains a problem, smart working is not possible and the rural area will never become an alternative to working from home (but an ultra broadband network of fiber optics should cover all of Italy within a few years).

The solution to save the rural areas and the shrinking villages is not on the horizon. As long as the population decline does not end, the chances of reoccupying the two million abandoned homes in the Apennines are not very high. The biggest dilemma is: lack of work.

Possibly part-time living is a provisional solution, also for foreigners. Residents have observed that there is a slight tendency to stay in the country side longer in the summer. Not just August, but from May to September. “Those who have a second home, and can work from home, try to extend the time in the country,” says Malaspina.

It could be a temporary solution. Depopulation villages are thus repopulated, even if only for about half the year.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Portrait of some of the (last) villagers

A mother’s hectic time schedule

Anna Maccellari (40 years old), part-time saleswoman, married to Fabio Castelli (not pictured), bricklayer, mother of Greta (10) and Sveva (6)

The only family with children in Cerignala is the family of Anna and Fabio. They live in a villa that Fabio himself built ten years ago. They have a large garden, which looks over the beautiful Trebbia Valley. "Fabio was born and raised in Cerignale," Anna tells me. "Because he has his job here, and he is so attached to the place, I followed him when we decided to get married." The wedding was held in the church of Cerignale in 2007." Presumably, they were the last ones. Six-year-old Sveva is the youngest resident of Cerignale. Anna works in a supermarket in Ottone, a municipality you can reach in 20 minutes by car. Sveva goes to the nursery in Ottone, Greta to elementary school in Bobbio, which is an hour away. This is Anna's schedule in brief: -7.30 to Ottone: Anna takes Sveva to the nursery, works in the store (an assistent from the village takes Greta to Bobbio in the meantime) -13.30 Anna returns to Cerignale -15.30 Anna picks up Sveva from school in Ottone -16.00 Greta returns from Bobbio (with the asssistent) -17.00 on Tuesday to Bobbio for Greta's volleyball lessons (Sveva joins the others) -17.00 on Wednesday to Genoa (one hour's drive) for Sveva's swimming lessons (Greta joins)

13 priests for 425 parishes

Aldo Maggi (65 years), parish priest

Don Aldo lives as parish priest in Bobbio and has his working area on the Trebbia River. It would be better to call him parishes priest. Let's go over his weekend schedule. He starts Mass on Saturday afternoon in Selva. That's an hour and fifteen minute drive from Bobbio. The next church service (4:30 pm) is in Orezzoli. Then on to Ottone (18.00). The schedule on Sunday: Bobbio (9 am), Marsaglia (10 am), Pieve di Montasola (11 am), give communion to a very elderly woman in Brugnello (12 pm), again Marsaglia (3 pm), Cerignale (4:30 pm), communion at the home of three bedridden people, Ottone (6 pm). Maggi will keep up this schedule for about ten more years, until his retirement. It is easy to imagine what happens after that. He will have a successor, who will have to serve an even larger area. Currently there are 13 priests active in this diocese (Piacenza). The diocese consists of 425 parishes. In the past you had at least one priest per parish. The average age of the priests is high: between 50 and 90 years, most in their 70s and 80s. Maggi's successor will surely no longer go to Ottone twice a weekend, and Cerignale, of course, he will leave altogether. Still, Maggi doesn't see the future as so bleak. He says he trusts in divine providence.

This content is not shown.

Click on this block to display all our content, by accepting our cookies or review our cooky-policy below.

Three practices, nine consulting times

Vera Lucia Mattoso (63), general practitioner

Every Friday Vera Mattoso from Bobbio comes to Cerignale in her little red car. She then has two hours of consultation time and makes house calls. Today she passes by a woman who has had a brain ischemia and suffers from diabetes. She also visits someone who recently had a tumor removed. Mattoso, who was born in São Paulo and has been working as a doctor in Italy for thirty years, combines her practice in Cerignale with those in Bobbio (where she receives five visits a week) and Marsaglia (three consultations a week). "If there is an emergency, an ambulance is sent from Ottone, about twenty minutes away, and the patient is taken to the hospital in Bobbio." If the situation is serious, the journey continues to the hospital of Piacenza (80 kilometers). In the event of an extreme emergency, a medical helicopter is sent from Parma (120 kilometers). According to Paola Remuzzi (70 years old), one of Mattoso's patients, if the emergency is severe, you are dead before the ambulance arrives. Yet she must confess that the ambulance has already brought some relief to her father (96 years old). Italy's public health system, which is well regarded internationally, does seem to work. For example, Mattoso writes prescriptions through a telematic system, whereby the patient can pick up medications from any pharmacist in the country. Too bad, though, that the nearest pharmacy is in Ottone.